paintings volume 6

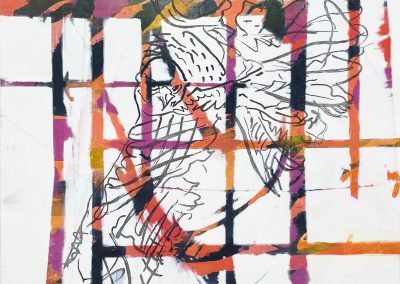

My current body of work, Avian Witness, has developed as part of my ongoing response to the growing divide between the natural world and the manmade environment. As our natural areas are shrinking, and climate is changing, I’m thinking about primeval forces such as animal migration, magnetic pull, and wind. As an abstract painter, I’m alert to powerful natural patterns as they intersect with the built landscape. Birds still migrate, yet often over vast built-up expanses of large cities. Herds of elk and deer move through the landscape in the fall, intersecting more frequently with fences and roads. As I travel between Montana and other parts of the West, I notice more game-crossing overpasses along well-travelled highways. That kind of human engineering for the sake of preserving natural patterns is compelling to me as an artist.

Click here to learn more

I took up the pursuit of bird hunting several years ago with my partner and our dog, really as a way to better understand the woods and the mountains, and to broaden my horizons. Indirectly but significantly, this experience has changed my thinking about art. Walking in the Big Belt Mountains, I stare down—so as not to trip—at the Pollock-like forest floor texture thick with kinnikinnick berries, moss, leaves and branches, but I’m constantly on alert for the unmistakable wingbeat of grouse. I’m not looking at landscape: I’m a part of it. It’s an aerial view, with the movement of birds constantly on my mind. In the bigger picture, bird population numbers and habitat are part of my growing awareness.

Back in the studio, between painting sessions, I make quick ink drawings of Western birds with my steel-nibbed pen—the type used since the 1850s to write with. Reading books such as Aldo Leopold’s Sandhill County Almanac, Richard Power’s The Overstory, Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire, and David Abram’s The Spell of the Sensuous have fueled my growing need to incorporate something from the natural world into my painting. Like many of us, I feel a great sense of loss regarding the natural environment. So how to move forward, how not to be “at a loss” as an artist?

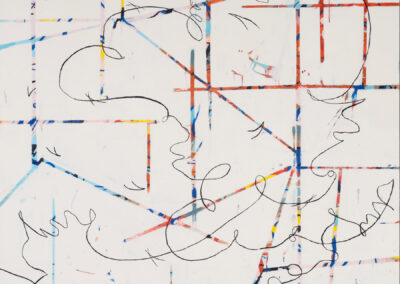

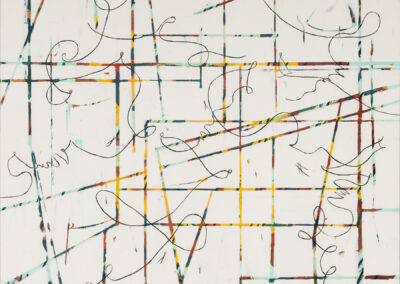

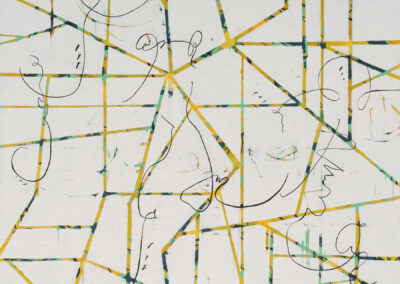

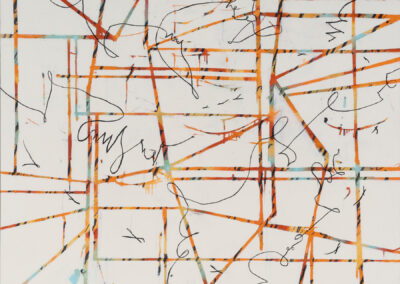

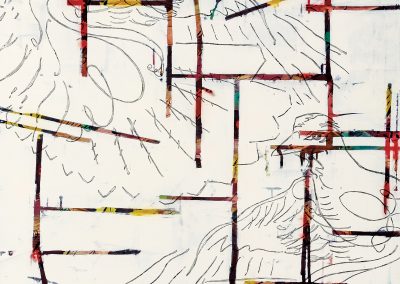

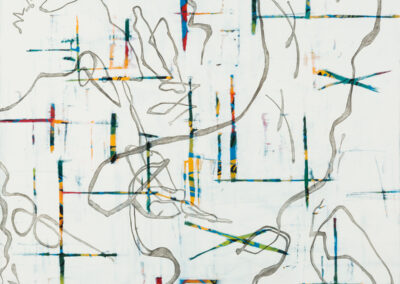

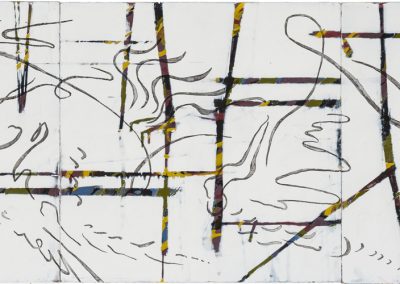

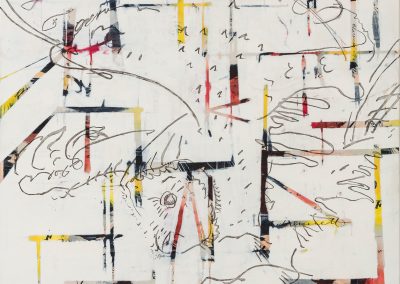

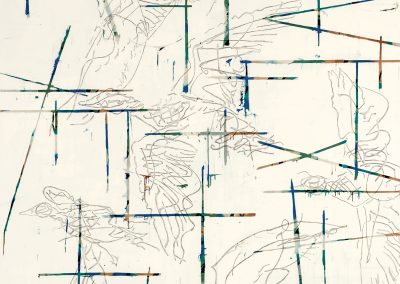

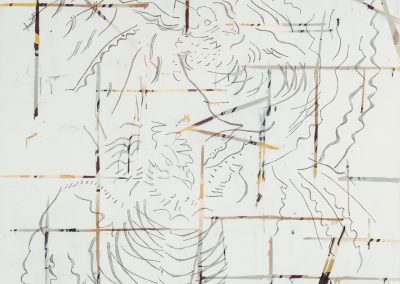

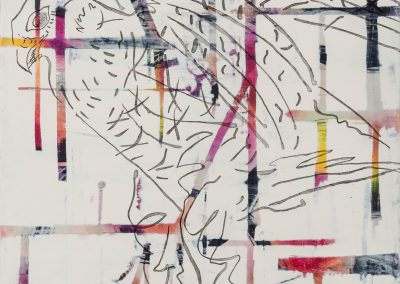

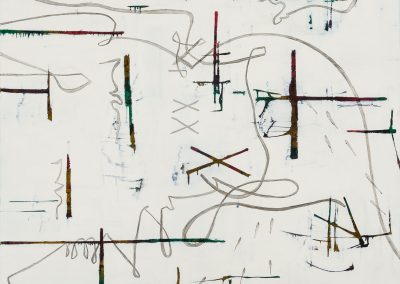

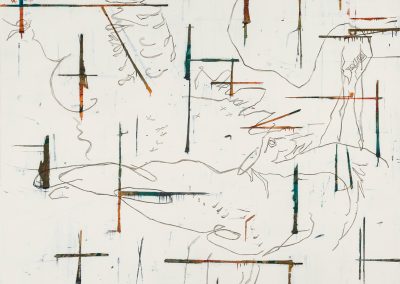

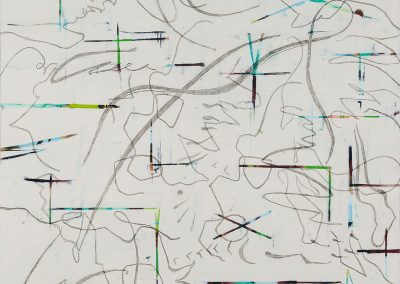

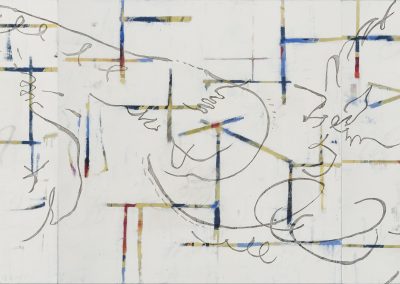

Making a painting in this series begins with a ground built up with layers of silkscreened handwriting fragments and gestural swooshes of color. I think of these initial layers as the literal “ground,” as of the earth, the landscape. Yet the layers are partially comprised of letterforms, which signal culture and human history. The angular patterns on upper surfaces evoke street grids, agriculture fields, and other manmade interventions. Skittering marks here and there elicit tire treads or heavy machinery.

My drawings of birds are the basis for the large curvilinear swoops on top of the rectilinear compositions. Slowly painted with translucent inky black, bird forms are not immediately obvious once transposed onto the paintings, but something of the movement of a bird in flight is transmitted. These black lines are not legible in any literal sense but instead evoke rhythms of nature.

By overlaying the geometric, color-filled slivers with flowing translucent strokes, a complex, polyrhythmic patterning emerges. The eye darts between the contrasting layers, which intersect almost randomly in an unplanned spontaneity. In making these paintings, I envision how such opposing systems of human development and natural forces might coexist in a harmonious ecosystem.